| ||||

Remembrances of

Late 19th Century Washington Heights:

Maximilian Waldau

Part 1

My father was born August 22, 1877, several blocks north of the Grinnell’s location. The family’s apartment faced uptown, he recalled, where small farms abounded. My father remembered raucous barnyard feeding times. There was always, however, plenty of fresh eggs and goat’s milk—excellent for making cheeses like “sikker” and “kochkäse.”

Dad also recalled that during winters, the Hudson River often froze solid, when he, along with brothers and cousins, joined gangs who felt compelled to protect their turf against tough, invading “Ho-buccaneers” crossing the ice from Jersey. The weapons of choice were slingshots (see David vs. Goliath) for which projectiles ) such as broken paving stones, were harvested.

As a boy, my father held a number of part-time jobs to earn pocket money. One of the more bizarre was hiding behind a monstrous turbaned-Turk marionette called Ojeeb the Magnificent that was located in Greenwich Village. Ojeeb’s task was to play chess against all comers. If Ojeeb won, Dad collected a dime; if Ojeeb lost, payment was zilch. A younger brother, my uncle August, was hired to shill for this faux Arabian-Nights wonder, until Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt clamped down on truancy when Dad and Uncle Aug were hauled back to school.

Columbia U’s freshman water-polo team used to scrimmage against a team from the Deaf-and-Dumb Institute, located near west 164th Street. My father never relished these practice sessions because the Institute’s swimmers, often quite a bit older, seemed insensitive, or aggressive, for they never seemed to realize just how long they could safely hold an opponent under water, a typical maneuver used to gain possession of the ball.

Present space does not permit elaborating on such adventures as shoveling snow during the blizzard of ’88, riding a horse-drawn trolley along Broadway, or acting as bat boy for the Giants baseball team playing on Coogan’s Bluff (after first sweeping peanut shells from the grandstand.)

Part 2

If, as a poet suggests, April is the cruelest month, then surely March is the most fickle. It was in March of 1888 that the malignant meteorological manifestation known as the infamous Blizzard of ’88 took place. The snowstorm lasted continuously for many days and nights, accompanied by a howling wind. As expected, city traffic was brought to a standstill. Streets, sidewalks, even first-floor windows were covered to over ten feet with the white stuff. Obviously, schools were closed, a cause for rejoicing among my father and his brothers, who went out armed with shovels, coal scoops, skillets, soup ladles, anything which could convey slush without spilling. They earned great sums (about 25 cents an hour) pushing accumulations this way and that, freeing doorways, building castles, carving out tunnels. On top of the heaps they stuck signs: “Fill your icebox—CHEAP! Make an offer. No bid refused.” Fortunately for the boys’ entrepreneurship, there was little money left in the city budget for snow removal as it had been misappropriated through municipal malfeasance by Tammany Hall, a political organization, named after the Tammany Indians. My father used to sing:

Tammany, Tammany

Big chief sits in his tepee,

Urging braves to victory.

Tammany, Tammany!

Scalp ‘em, swamp ‘em, get the wampum.

Tammany!

Then as in the early 20th Century and until recently, New Yorkers were in the habit of moving every few years, mainly to take advantage of a fresh paint job that came along with any new digs, forcing oneself to do some housecleaning.

One memorable occurrence took place when the Waldau family moved from its third floor apartment to the third floor of an adjacent building, separated from the first by only one small air shaft. It was exceedingly onerous to lug furniture down three flights of stairs, across a tiny stretch of sidewalk, then up three narrow flights. Much labor could be saved by swinging burdens across the air space by a rope suspended from the roof.

“Hey, Jack (my uncle John)! You have the bed?”

“Got it.”

“Okay, Kip (Uncle Carl). Tie on the player piano attachment good and tight.”

(This last was important, because my dad later courted my mother, who lived in the apartment above, with this contraption, played with great feeling (according to Dad). The melodies wafted up through a hot air vent in her floor-boards. In a sense, both my sister and I are products of their musical moments.)

Of course, all this trapeze-like moving was accompanied by much shouting and several mishaps. All went along some-what smoothly until an aggrieved gentleman with white whiskers came out of his apartment on a lower landing to cry, “Ich glaube mir wir versperren jetzt!” (loose translation: “Enough, already!”) In years to come, it was amazing and amusing to hear aging men at family reunions chortle with relish recounting their youthful escapades.

Naturally, every family has its scandals or shameful secrets, which never seem to die but are passed on, in whispers, from one generation to the next. One such tale concerns a female relative (who small remain nameless), known to like her little nip of schnapps on occasion. She was asked one day to baby-sit with one of my infant uncles as my grandmother had to leave on an important errand. Apparently, Tante ______ wanted to be more than helpful for she bundled up the garbage to be left outside. Unhappily, she also bundled up my baby uncle and placed him side by side with the garbage on the kitchen table. Grandma, thankfully, arrived home in the nick of time to avert a mishap.

My father’s father died when Dad was about nineteen. It was decided therefore that, as he was the eldest, Dad would interrupt his education (he was the first to admit he had never been much of a scholar) to help with the family’s finances. He got a job selling cash registers, and ended up working for the same company for over half a century—having left one position because a boss insisted he attend Episcopal church services regularly. For his new job, he needed a horse and buggy. The horse was named Bob; Bob groaned and wheezed through the whole workday. Indeed, Dad had to help Bob physically pull the buggy over the slightest up-grade. It seemed the only time Bob enthusiastically moved was close to quitting time, when his ears perked up and his nostrils flared as he trotted happily toward the livery stable (Bob also relished feedbag time).

Dad once had an actor as a trainee, filling in time “between engagements.” Soon, the actor gave up—Dad always claimed he was one of the Barrymores—and growled “Cash registers and a—holes are similar. It appears everyone has one!”

Over the years, I was compared unfavorably to the horse. “Try to correct your dilatory habits, Sonny. Show some gumption. Don’t become like old Bob, for God’s sake.”

In 2000, Roy Waldau, long-time resident of the Grinnell wrote two articles for the Grinnell Gazette, a Grinnell newspaper. These articles recounted memories his father Max Waldau had passed along of life in lower Washington Heights before the turn of the 20th Century.

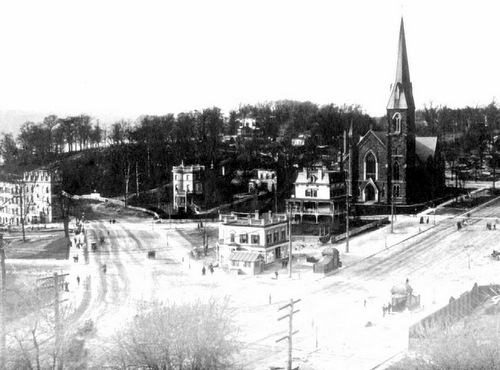

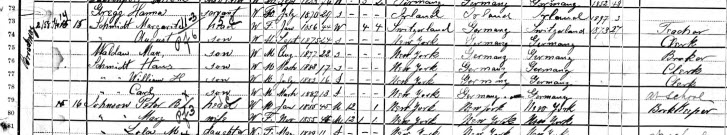

Since then, Mr. Waldau's family has learned through genealogical research that during the 1900 census – just one month after subway construction began at Broadway and 157th Street – Max Waldau was living at the corner of 158th Street and Broadway, only a half block from where the Grinnell stands today (see picture at right).

At left: A 1968 photograph of Roy Waldau and his son Al, a current Grinnell resident.

Broadway between 156th and 158th Streets in 1905

The house in front of the church is most probably the one where Max Waldau was living in 1900.

(For a larger view, click the picture)

1900 Federal Census, showing Max Waldau (4th line from top) living at Broadway and 158th Street; his occupation is listed as Broker.

| ||||

Our Stories: Remembrances of Late 19th Century Washington Heights: Maximilian Waldau Written by Roy Waldau

The residents of 800 Riverside Drive celebrating community, a unique sense of place, and an architectural gem